From March 27 to April 1, the Youth Leaders Multilateral Workshop on Global Youth Agenda was held in Beijing, bringing together youth from various international organizations to promote collaboration toward achieving the SDGs. Noriko Komatsu, vice chair of the Youth Peace Conference of the Soka Gakkai, presented on the organization’s peace efforts. On March 28, the International Symposium on Transforming Education for Girls and Women in the New Era: Inclusion, Equity, and Quality was also held in Beijing. Tetsuko Watanabe, a member of the Soka Gakkai Academic Division and lecturer at Soka University in Japan, spoke on the importance of humanistic education.

On March 27, former president of Ireland Mary Robinson visited the Soka Gakkai Headquarters in Tokyo. She met with Senior Vice President Yoshiki Tanigawa and the chairs of the Soka Gakkai’s Peace Committee and Women’s Peace Committee. Ms. Robinson was in Tokyo to meet with organizations working on climate issues. As chair of The Elders, an independent group of global leaders working for peace, justice and sustainability, she stressed the urgency of addressing existential threats including climate change and nuclear weapons, emphasizing the important influence of faith actors.

Living Buddhism: Judy, thank you so much for speaking with us today. You’re a published author, poet and essayist. How has Buddhism helped you realize your potential as a writer?

Judy Juanita: Well, thank you. About potential, I’ll start by saying—it isn’t everything. A single vice can deadlock a person of great promise. I saw this early on in my father, a graduate of Langston University, son of one of Oklahoma’s first Black oil millionaires and, as a Tuskegee Airman, among the first Black aviators in the U.S. Army Air Corps. But in this last achievement, he picked up a gambling habit, which he brought home from the front during World War II.

Though he was in many ways a superb father, this vice of his would often turn our home into a battle zone. When he lost at the racetrack, he’d take his anger out on us, pawn household items and leave the family finances in tatters.

It was my mother, a hardworking civil servant, who always picked up the pieces. From her I heard no end of complaints against my father, but that wasn’t all I heard. She was always spinning stories, telling tales; a passion for stories I believe I got from her. But the way of the gambler—the light-hearted certainty that, for the brave and gifted, life was full of shortcuts to success—this I may have gotten from my father.

What did that look like for you as you got older?

Judy: I was so full of energy, moving at 90 miles per hour. As a member of the Black Panthers, I saw myself as a revolutionary and had nothing but scorn for 9-to-5 jobs and the careful day-to-day plodding and scrimping of the people who worked them.

Any room I walked into, I was fairly certain I was the smartest one in it. Whether or not I really was is another matter. I talked a good game and could move a crowd.

“You’ve got a tongue like a pair of scissors,” my father used to warn me. But I zipped around with that pair of scissors, my “murder mouth” as it was called back then, making my own way through society, snipping shortcuts, I thought, straight through its fabric.

Like my father in his 20s, I had a few impressive accomplishments beneath my belt, all on account of my quick mind and quicker tongue. In every aspect of my life, I moved quickly.

In June 1968, at age 21, I married, became pregnant that fall and had a baby boy in the summer of 1969. My marriage gave me some stability, but I was still the same Judy.

“Oh, Judy,” my friends would say, “she doesn’t need drugs—she’s already high!” They meant to say I was a good time, a free spirit, and it’s true, I was. But they meant something else as well—that I was ditzy. Money, budgets, rules—all these were the worries of other people, the squares and the rubes. Not my concern. I mean, I’d simply lose money or leave the house without enough in my wallet. In either case, my level-headed husband was the one who picked up the pieces. That is, until he wasn’t. My lapses of carelessness enraged him, and one day, he had enough. I was 31 when we divorced and was suddenly on my own, working as a freelance journalist, a single mother with a rambunctious little boy.

A tight situation.

Judy: Mm-hmm. No quick and easy way out of that one; no more running from myself. On welfare, food stamps, in Section 8 housing, I was fighting losing battles on every front. If I kept the car running, I couldn’t pay rent. If I paid rent, the lights would get shut off. If I paid the electricity bill, the phone line would get cut. If I paid for the phone, they’d cut the gas.

Deeply frustrated with the end of my 10-year marriage and under immense financial pressure, I began to release my frustration as my father had when he’d lose at the racetrack. I would harshly punish my son.

When did you realize you needed to course correct?

Judy: Out for coffee with a friend one day, I mentioned that my car was in the shop. It was always in the shop, it seemed, because I was always getting into accidents. As I explained this to her, her eyebrows hitched higher on her forehead.

“I want to make sure I heard you right: The car is always in the shop because you’re always getting into accidents?” she asked.

“Well, yeah,” I said, “but, it’s not like I ever get hurt. I’m lucky that way, you know.” I shrugged it off, laughing, but she wasn’t laughing with me.

“Listen, I don’t want to hear you use that word lucky,” she said. “You’re not lucky, you’re fortunate. But you’re burning up that fortune fast—the way you’re living, you might already be running on empty.”

This was on a Friday that she said this.

“Tomorrow, I want you to wake up, shower and dress like you’re going to the office, but come to my place. We’re going to build some fortune.”

I’d never been to her apartment, but it was a real treat, unlike any apartment I’d ever been to. Almost like a little palace. There, facing the Gohonzon, she taught me how to chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo.

“What do you need most?” she asked.

“Housing,” I said right away.

“Then let’s chant for housing.”

I kept on chanting and, within the month, landed what felt nothing short of miraculous—a little “palace” of my own, what they call on the East Coast a “railroad flat,” an apartment that runs the building back to front, the rooms connected by a long hallway. Of course, I kept chanting after that, but I thought Nam-myoho-renge-kyo was something of a rabbit’s foot—a good luck mantra to fulfill material wishes. I didn’t understand at all the concept of human revolution. I dabbled in the practice for some years. Eventually, I came to a meeting and was struck by the straightforward rationality of Buddhist concepts.

Did you begin to apply Buddhist practice more deeply, to engage your inner life?

Judy: Well, yes, but slowly, almost without realizing. I’d listen to people give their experience about how Buddhism had transformed their life, and I had the same scorn for most of them as I’d had for most people who went through life at a slower, steadier pace than I.

One experience I remember was from a young man who chanted to get a job as a florist. He’d gotten that job, and he went on to describe how much joy it gave him to arrange the flowers in their vases. I remember thinking: What? That’s nothing! And yet, beneath the derision, almost unnoticed, my heart was moved, if even just a little bit, by this experience, by the sincerity of the young man who gave it. His rich inner life nudged me to consider the state of my own.

When did you begin to practice in earnest?

Judy: It was when my son, just a few months into my taking up a steady practice, confronted me. I gave him a smack, and he said to me, with all his little self, “I’m tired of you slapping me around.” In that moment, I realized that there was something wrong with me—not with him or the world or other people, but me, my inner life. My son had told me, in his way, that I had some deep inner work to do. Because I was chanting, I really heard him.

I dove deeply into my Buddhist practice, seeking tutelage for the first time in my life, from Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, Josei Toda and Ikeda Sensei.

This opened me up to seek tutelage in other areas as well. As a writer, for instance. I’d always considered myself one of those rare breeds of writer—a natural. I had a chip on my shoulder. It took the positive functions in the universe to take me by the scruff of the neck and sit me down, as it were, for a talk, for me to really listen.

It’s as if they were saying: “Slow your roll, sister. You’ve got a lot to learn before you can become all that you think you are. … You’ve got to slow down so you can appreciate greatness.”

I was inspired by Nichiren’s writings, where he states, “Whether you chant the Buddha’s name, recite the sutra, or merely offer flowers and incense, all your virtuous acts will implant benefits and roots of goodness in your life” (“On Attaining Buddhahood in This Lifetime,” The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 4).

In chanting daimoku, cleaning our Buddhist center or making a financial contribution, all my actions began to reflect and strengthen the great inner life condition of Buddhahood. Financial contributions were especially profound for me, since they required me to deeply consider my own relationship with money and deepen my faith in the causes I was making for the sake of Buddhism.

My son, when he left to live with his father at 15, gave a toast at his farewell dinner. “Thank goodness I’m getting out of here,” he said. “Buddhism is for people with bad luck.”

Though our home life had become lively and fun, my war with bills lasted for many years, and financial hardship was an inescapable part of it. I thought about his comment for years, and it spurred me to win, to show actual proof of the power of the Mystic Law and my own abilities, not only as a writer but as a human being. Even in times of financial hardship, I did my best to contribute what I could during the May Commemorative Contribution activity out of deep appreciation for having encountered a great mentor and philosophy that was helping me emerge from my arrogance as a more thoughtful, more present person.

Would you say this transformation has also affected your writing?

Judy: Mm-hmm. The greatest benefit has been that I know how to deeply appreciate life. No longer considered the ditz or the speed demon of the family, I’m the rock, the one people can rely on in a time of crisis.

On my 60th birthday, in 2006, my son stood to give another toast, this time to my character. He’s not one to jabber, but he just went on and on about how much value I’d created and was creating with my life.

The character arc of the protagonist of my novel Virgin Soul goes from being selfishly concerned with her own opinions and desires to someone who is concerned about other people. My greatest achievement in life—and I absolutely credit my Buddhist practice—is not that I was successfully able to write about such a transformation but that I lived it.

These days, I work as a full-time professor at the University of California, Berkeley, teaching youth who are undergoing significant transformations of their own. I stopped looking for shortcuts to glory long ago. Instead, I learned to search for heart-to-heart connections, giving praise to the great potential inherent in all life. This, I’ve found, is the shortest, surest route to happiness.

On January 31, Asle Toje, deputy leader of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, gave a talk titled “The Nobel Peace Prize: Can It Influence World Peace?” at Soka University of America in Aliso Viejo, California. Living Buddhism sat down afterward with Mr. Toje to discuss the SGI’s role in contributing to world peace.

Living Buddhism: Hello Mr. Toje, we look forward to discussing fundamental issues facing humanity. Where do you think the SGI stands as a peace movement?

Asle Toje: During the Cold War, there were many peace movements out there. Go to the center of any major Western city and you’d see [them] out in force. Now, the rapidly rising tensions between the great powers has increased the chance of nuclear war, but where are the peace movements? Nowhere to be found. Many of the peace movements of the Cold War have withered.

Soka [Gakkai] is one of the few examples of a peace movement that has not withered. This is no small thing. From its inception, Soka [Gakkai] has focused on the nuclear issue because of Japanese history and Josei Toda’s experience,[1] which allowed it to become one of the few organizations during the Cold War that was equally at home in the East and West. So, Soka Gakkai is one of the great peace movements in the world today. It’s a juggernaut, cannot be ignored. I think its members should have some self-confidence on that score.

What are your thoughts on Daisaku Ikeda as a peacebuilder?

Toje: Daisaku Ikeda is special, isn’t he? As a peace philosopher, he’s one of the best. I think one of the great problems is that in the West, the powerful have persuaded themselves that they’re going to “contain the Chinese” and “confront the Russians.” Where will this lead? To war. And with war among the great powers, there’s a very great chance it’ll be a nuclear war.

On the other hand, Mr. Ikeda’s peace message is one of charity and dialogue. I find the message that he conveys in his annual peace proposals[2] immensely useful. He’s given global issues serious thought and understands international relations, often better than our political leaders.

In his 2006 peace proposal, Daisaku Ikeda quotes the definition given by philosopher Jose Ortega y Gasset of civilization as “the attempt to reduce force to being the ultima ratio [last resort].” In a world in which force is used so readily, what can we do as private citizens to create a society without war?

Toje: Each of us has to get up and move. There are so many things that we can do with our days, and there are so many worthy causes that one could be involved in. I make the claim that the most important thing that a peace movement can do is to stand up for peace—and it’s not easy. It was never easy.

We got a bit lazy. We got a little too comfortable. And the fortitude that Mr. Ikeda preaches—to prepare yourself—is perhaps a call to those in the movement to prepare for tumultuous times ahead, because the message of peace has never been more controversial. For example, in my own country, simply advocating peace talks between Russia and Ukraine invites the most horrendous accusations—of being a traitor or a spy.

We must be ready to make sacrifices and to create a peace movement that is visible. The majority of people want peace. Many in power, however, still believe that war can resolve issues. We’re at an inflection point of human history now. This is where it gets difficult because we invented nuclear weapons. We used them, we were horrified at the result and for 50 years or so, there was a memory that was kept alive that created a huge taboo against their use. During the Cold War, the superpowers occasionally thought about it, but this taboo kept us from stepping into a new, devastating reality.

We need to reinforce the nuclear taboo and make our voices heard. In order to do that, we need to go out and persuade people with whom we might disagree on very important things. But this sort of crazy mindset has taken hold in the West, where people say, “I cannot have a dialogue with you because you’re a [fill in the blank],” or whatever. And it’s not like that, is it? We go into the world and make our case, politely, insistently, with humility in the belief that an honest word of truth can never be spoken in vain.

Daisaku Ikeda is 95 years old and has been calling on the younger generations to stand up and continue his peace work. We honor him. It took him a lot of guts to go to the Soviet Union and China in the 1970s.[3] It wasn’t popular in Japan at that time. And now it’s time for us to show our colors, you know, to fly the flag of peace. And me as a Lutheran, I welcome standing shoulder to shoulder with my Buddhist family on this.

Daisaku Ikeda recently called for nuclear weapon-states to adopt a No First Use policy. However, some, including the United States seem hesitant to make such a pledge. This seems to be rooted in a lack of trust. How can trust be developed in the international arena to more successfully implement regulations on nuclear weapons?

Toje: No First Use is a stopgap to prevent ourselves from plunging into darkness. It’s the lowest ambition thinkable. If we had this discussion during the 1970s everybody would say: “No First Use? Of course.” China and India have No First Use policies in place. We need to pressure the other nuclear weapon-states to accept that No First Use is the least we can expect from a responsible nuclear power. Now, we’re in the new nuclear arms race. The Chinese are doubling their arsenal; the Americans are revamping theirs; and the Russians are basically threatening to use theirs. So, I think that we need to speak out for humanity. There must be someone who speaks out for us as a species. We need more leaders like Mr. Ikeda, who paint the bigger picture: that we want to have a planet that we as a species can inhabit.

We must seriously consider the Fermi Paradox, named after Italian-American physicist Enrico Fermi, who, in the summer of 1950, walking to lunch with fellow physicists at Los Alamos, posed the question: Why hasn’t our planet been visited by other intelligent life? One potential conclusion was that civilizations destroy themselves before they master intergalactic travel; that intelligent life is something dangerous, destroying [its home planet] before it can leave it. We need to consider the big picture, and that is that we need our planet to survive. Unfortunately, this perspective is rarely heard—we’re all caught up in the prevailing logic of geopolitics: our side against theirs.

This is why, I imagine, Mr. Ikeda built the structure of the SGI. As one of the largest intact peace movements in the world, your number’s been punched; this is your time. The job has been left to you, and me. We can’t sleep on this, can’t afford to. We can’t simply be concerned with our own spiritual enlightenment but need to go out and speak with others. This is your time, and this is your world.

On March 25, an interfaith symposium organized by the Madrid Association for Interreligious and Intercultural Dialogue [tentative translation] was held at the Soka Gakkai of Spain center in Rivas-Vaciamadrid, Madrid. Dr. Juan José Tamayo, a theologian and professor emeritus at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, gave the keynote speech on the importance of nurturing compassion in every aspect of society.

On March 18, Soka Gakkai youth from Tohoku organized a seminar at the Tohoku Culture Center in Sendai, marking 12 years since the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami. The seminar was part of the “Soka Global Action 2030” peace initiative. Soka Gakkai Peace Committee Executive Director Nobuyuki Asai introduced relief activities conducted by the organization after the earthquake. Dr. Sébastien Penmellen Boret, associate professor at the International Research Institute of Disaster Science at Tohoku University, affirmed that people-to-people ties in local communities play an important role in times of disaster and noted the value of the Soka Gakkai’s daily activities and network in this regard.

by Heidi Hayashi

Stratford, Conn.

My mother and father were opposites; my mother warm and gentle, my father strict and demanding.

“We’ve given up,” my father would muse, “we might as well be two different kinds of aliens.” But he said this with a little smile. Somehow, though worlds apart, they’d struck on a kind of peace and, baffled by each other, went ahead together nonetheless.

My mother, born and raised in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, had come of age in New York, while my father, the son of a Taiwanese oil painter, immigrated to Japan as a boy with his family after World War II. He graduated university in the states, in Chicago, then moved to Manhattan where he met my mother. When his work called him back to Japan, my blond, green-eyed mother came with him, bringing into my father’s life the Buddhism of the SGI she’d embraced in New York.

Growing up as the daughter of these two people from two different worlds, in a country where I knew no one who looked like me, I was in a constant identity crisis. Who am I? I wondered. Who is Heidi? Though I didn’t have an answer, I knew at least who my father expected me to become. The words he shared most often with me and my brother were, “Get into a top school and top company!”

For my mother’s part, her favorite words were, “Winter always turns to spring” (The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, vol. 1, p. 536).

This passage took on new meaning at age 12, when a medical fluke during a routine procedure robbed my mother of her life. It was like the sun had fallen out of the sky. My father, who’d taken up Buddhism while my mother was alive—somehow agreeing on the point of kosen-rufu when he’d hardly agreed with her on anything else—abruptly stopped practicing and began drinking.

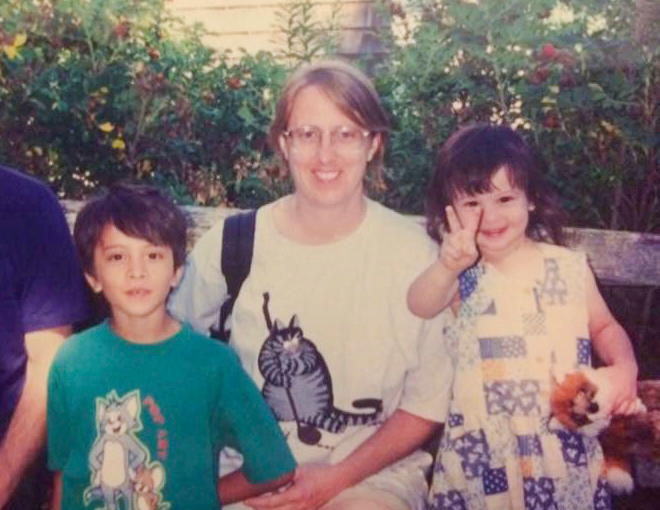

Photo courtesy of Heidi Hayashi.

Her death invited all kinds of hardship into our little apartment. My father was often filled with resentment and rage; the medical lawsuit he filed put us on the financial edge; and he developed a severe health problem requiring open-heart surgery. My paternal grandma moved in to help out; the two of us shared a room until I graduated college. She was deeply opposed to my Buddhist practice, which, thanks to my mother’s friend who visited me every day for months, I took up more seriously.

With everyone around me going through so much hardship, it actually never occurred to me to chant for myself. The least I could do, it seemed to me, was to chant for their happiness and to fulfill their expectations. I did, indeed, graduate from a top university in 2018, and immediately landed a job at a major company. I was the person my father had expected me to become, but it came at a cost I found I couldn’t pay.

As the new employee, whatever work the others didn’t want, they dumped on me. Sleeping only three or four hours a night, I chanted a couple minutes in the morning, just enough to summon the will to get into my business suit and out the door. At the train station, I let the crowd carry me aboard, but as I approached the station near work, I felt I was about to throw up.

When she saw that I could no longer smile, my mother’s friend begged me to seek guidance from a senior in faith.

As soon as we sat down, I burst out: “I’m trying my best!” and then broke down in tears. Actually, I was crying so hard that I couldn’t see the leader’s face. But a kind voice asked: “Heidi, no one would say otherwise. But what are you doing your best for? For what purpose?”

To that, I didn’t have an answer.

At home, I went to the Gohonzon and started from zero, chanting with the open question, “What is my purpose?”

From this prayer came another, quiet at first but then with greater conviction: I want to be a bridge between cultures, to open people’s hearts and bring them together. As my mother had been in her way, I wanted to be a bridge between the people of the U.S. and the people of Japan. Within the year, I left my megacorporation job and moved to the U.S. to live with my aunt in Cape Cod before finding work in New Jersey.

There, I took on chapter leadership and joined the Kayo Core, a young women’s training group. The thing about the core that struck me was the emphasis on personal goals. Eventually, I wrote mine down: Hopefully, I’ll get a job that I love, where I can put my talents to use to bring cultures together.

Hopefully…

One home visit changed my approach. I was visiting a young woman who had a dream she did not believe she could achieve. “You can do it!” I told her. But as I said this, I realized I was stressing the “you.” She heard it, too, I think, and we both had the sense that I was not convinced that I could achieve my own dream. This shook me up. How could I encourage another person if I didn’t believe in myself?

I began to get really serious in front of the Gohonzon about winning for myself as well as for others, which is what Buddhism is really all about. I crossed off the word hopefully in my prayer book; to encourage others, I was absolutely going to score this victory for my life, based on my dream, based on my vow. This was in 2022.

Soon after, a company recruiter reached out with an offer. I’d never heard of the firm, but the job description seemed as though it had been tailor made with me and my dream in mind—I’d even get to travel to and from Japan!

As it happened, the interviewer was Swiss. Upon meeting face to face, I could see he was puzzled, probably wondering, Who is this person, born and raised in Japan, with a Swiss name like Heidi?

“How do you deal with stress?” he asked.

“I like to run and … I practice Buddhism!” I burst out. His eyebrows jumped. He wanted to know more.

I landed the job, and I love it! My uniqueness, I’ve come to realize, is my greatest strength. I don’t have to be somebody else. I’m Heidi! Even in some small way, I’m going to bring people together and encourage them, as my mentor, Ikeda Sensei, has done, winning just as I am.

When we run up against trouble and find ourselves facing adversity, we may think we’ve reached our limit, but actually the more trying the

from Ikeda Sensei (The New Human Revolution, vol. 22, p. 359)

circumstances the closer we actually are to making a breakthrough. The darker the night, the nearer the dawn. Victory in life is decided by that last concentrated burst of energy filled with resolve to win.

From March 10 to 12, the World BOSAI Forum 2023 (International Disaster and Risk Conference) was held in Miyagi Prefecture, Japan. Scholars and civil society representatives discussed how to promote the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030. On March 12, Musicians Without Borders (MWB) and SGI (Soka Gakkai International) co-organized a session titled “Approach to Psychosocial Recovery after Catastrophic Events.” Nobuyuki Asai, director for Sustainable Development and Humanitarian Affairs of the SGI , presented on the Soka Gakkai’s “Building Bonds of Hope” concert series in the Tohoku region of Japan. The initiative began following the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami, and its volunteer choirs and orchestras have performed in other disaster-stricken areas in Japan including Kumamoto, Okayama, and Hokkaido. Fabienne van Eck, regional program manager for the Middle East for the Musicians Without Borders (MWB), introduced MWB’s music teaching curriculum used in post-conflict situations, and Professor Takeo Fujiwara of Tokyo Medical and Dental University spoke on the impact of adverse childhood experiences on children’s mental health.

From March 6 to 17, the 67th Session of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW67) was held at the UN Headquarters in New York. On March 9, the SGI (Soka Gakkai International) hosted a parallel event titled “Women’s Leadership for Human-Centered Technology,” at which Ivy Koek of the SGI Office for UN Affairs served as moderator. Representatives from the event’s cosponsors—Isabelle Jones of Stop Killer Robots and Dr. Kristen Ali Eglinton of the Footage Foundation—and Paloma Lara-Castro of Derechos Digitales discussed topics including the digital rights of women and girls. During the March 14 CSW67 session, Ms. Koek reported, in her capacity as Vice-Chair of the NGO Committee on the Status of Women in New York, that the committee had submitted five key recommendations to CSW67, informed by over 700 global consultations and surveys, and called on the commission to make gender-based violence a standing agenda item.

by Garrett Morris

Los Angeles

It didn’t help that my grandfather was a particular kind of minister—the kind that preached against sexual license on Sunday but practiced it liberally during the week. The problem was, I felt no less a hypocrite singing praises in the pews; I just never could swallow what was being dealt from the pulpit, about a God, somewhere out there, who was gonna save me. In any case, in my early 20s I turned my back on my grandfather’s church, turned away and didn’t look back.

For all its faults, the Christianity of my childhood was still, without a doubt, a kind of system. My own personal belief—beautiful in its way and free of dogma, was nonetheless just that—a personal credo: I have the power within me to realize my dreams! It carried me far, this motto—far from slow, churchgoing Gert Town, the little New Orleans burrow where I was born, and far in terms of my dream of becoming an actor, screenwriter and singer-composer.

By 1975, I’d studied intensively under a Julliard School of Music professor, been involved in a number of Broadway and off-Broadway shows, produced a play of my own and had landed work on a little-known show called Saturday Night Live as one of its seven original cast members. But my belief wasn’t organized in any way, wasn’t part of any kind of system.

Like a sailor setting out to sea without a compass—I began to drift. My first cocaine high was a beautiful one—it felt like empowerment, like I was at the helm, steering the ship of my life. But the feeling lasted only 15 minutes, and I was back to myself again, no more in control of my life than I’d been a quarter hour earlier. By the time my tenure ended at SNL, I was in my early 40s and a cocaine fiend. I came to Los Angeles and brought the habit with me. It’s ironic that, though something of a household name, I never felt quite at home with myself.

Through all the ups and downs of my career, I never stopped seeking a spiritual life. Even alongside drug use, I schooled myself in karate, receiving my black belt, and explored meditation and positive psychology, which were wonderful, helpful things. It was only natural that I found myself in conversations with others who were similarly inclined.

I’d met Art Evans, a fellow actor, and his wife, Babe, in New York, in the ’70s. I met them again in Los Angeles and was struck as ever by the sincerity and joy with which they carried themselves through life. They shared with me a Buddhist mantra, a chant: Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. This Law, they explained, was operating all the time, in all things, neither above me nor below me but within me and within all life.

I chanted with them from time to time, and to myself, too, and it felt good: positive and rhythmic. Like the lotus flower, which blooms and fruits at the same time, I felt the effect of chanting immediately. However, I wouldn’t immerse myself in the practice for some 20 years after my friends planted in my life the seed of Buddhahood, the wisdom of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo. In that sense, I was more like the oak tree that waits a good while underground before it comes on up out of the earth. Not until I hit a real rough patch—a painful divorce in 2001 and a dry spell of work, did I decide it was time to take up Buddhism in earnest. I’d become uncharacteristically negative—argumentative and downcast. When I spoke with my Buddhist friends, however, my negativity melted away. We just kept on talking, them and me, on walks, over coffee, on the phone; and I kept on chanting here and there and then more and more often, realizing, little by little, that Buddhism was what I’d been looking for, what I’d believed in all along.

In 2005, at the age of 69, I ended a 35-year relationship with cocaine and haven’t touched it since.

One day, my Buddhist friend and I were talking, and I said, “You know, I think I’d like to get the Gohonzon.”

“All right,” he said, “I’ll help you.”

I received the Gohonzon in March 2009 and on the day I joined did gongyo twice in one day for the first time, morning and evening. The next day I did the same, and the next day and the next. Chanting in rhythm with the day gave me a sense of what it was to practice this Buddhism as a practical system, as something more organized and substantial than my own personal creed or idea. Chanting in a consistent way hitched me up to the rhythm of the cosmos, to the visceral feeling in the depths of my life that there is a rhythm, or a Law of the universe—the Law of cause and effect—and it is active in me as much as in another, as much as in a grain of sand or a blade of grass. As my mentor, Ikeda Sensei, says: “I am not obliged to fall into decline. I am not obliged to be miserable. I have a right to be happy. The honest and true have a right to triumph” (Men Shining With Youthful Brilliance, p. 26). To me, my mentor is saying that if you’re about truth, if you’re about living with a deep reverence for life, then you’re not obliged to suffer; actually, you’re obliged to be happy.

It’s true that old men have a reputation for waking up grumpy, but chanting in the morning, I get my day on course, on the course of positivity, self-control and happiness. In 2012, I found a wonderful partner, a beautiful lady named Kimberly. More recently, I was nominated for a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame and landed a role tailor-made for me, on a show set in the shelter-in-place phase of the pandemic, which doesn’t require me to move around too much. All this is nice, but the important thing is that we keep in rhythm, the universe and me, that I move through the day a happy person, connected with others at the deepest level, where beats the rhythm of life itself.

What advice would you give the youth?

Garrett Morris: Sometimes what you’re chanting for will happen right away, like a lotus flower fruiting and blooming at once, sometimes like an oak tree, taking its time. The important thing is to keep on keeping on, getting in rhythm with yourself and the universe, morning and evening.