by Lela Shepley-Gamble

St. Louis, Mo.

I had a lot of what they call cognitive dissonance. At 37, I was one of the youngest female senior vice presidents at my Wall Street banking firm. Making lots of money, living in a New York flat overlooking the Hudson, traveling the world on the company dime, I was, according to my friends, a wild success. And yet something was missing, and that something was an answer to an existential question: What am I doing here? And not just “here” at the firm, but “here” on this planet. There were lots of causes and charitable organizations I believed in, and having the means, I’d given money to many of them but never was convinced I was making a dent.

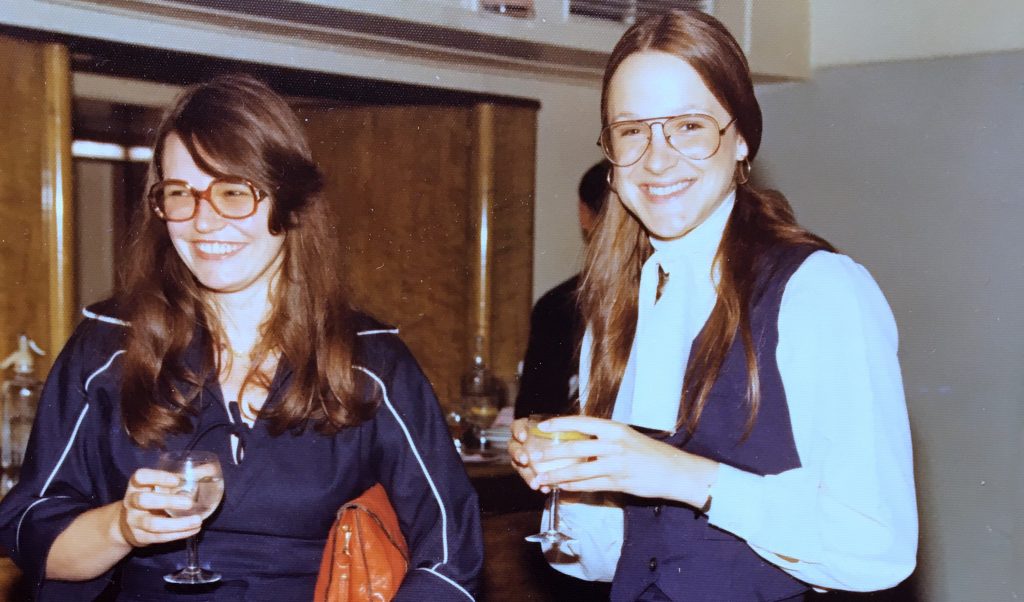

In 1987, I was invited to the 20-year reunion of a summer camp I’d attended every year from ages 12–17 in southeastern Ontario, Canada. Memories came flooding back, of canoeing through pristine wilderness, camping under stars by cook fires, loons calling wildly in the night. Algonquin Park was about as far from city life as I could get, and I figured the trip would do me good.

Bonds formed during adolescence are strong. Among those I had the pleasure to reconnect with was Rob Gamble, whom I’d dated my last summer at Algonquin. I discovered he now lived on the lake as its resident handyman, in a cabin without running water, electricity or road access. A simple, honest life he’d built, but I couldn’t help but notice that he drank too much and was looking rough. I left feeling concerned for him but also resolved to return to Algonquin, kicking myself for having removed such a place from my life. The following summer, I vacationed there, and Rob, making his rounds, came by. I could tell right away he’d stopped drinking. He was bright and grounded. We sat down for tea.

“Rob,” I ventured, “what’s different?”

“Buddhism,” he said.

Apparently, soon after the Algonquin reunion, while making his rounds, he’d knocked on the cabin door of a resident Buddhist. As at the reunion, he’d been keeping up a steady drinking habit, battling depression and stress, which had robbed him of sleep. He didn’t look good and the Buddhist at the door said so. He replied that he felt the way he looked.

“Well then you come inside and chant Nam-myoho-renge-kyo,” she told him. His first benefit came swiftly—while chanting, he fell asleep for the first time in days.

Speaking with him now over tea, he asked if I’d like to come to a meeting. I looked him over once more. The change was indeed real. “All right,” I said.

What I heard at that first meeting fell on my ears like water on parched earth. I learned that everybody has a Buddha nature—wisdom, courage, compassion, vitality—available at all times, waiting to be tapped. Then! I heard about the law of “cause and effect”: The energy we put out is the energy we get back. And then! The concept of “the oneness of life and its environment”: A rejuvenation of the human spirit is linked precisely with the rejuvenation of communities, societies and the natural world.

It’s about people, I realized. Real meaning and change are found in the rejuvenation of people.

When I came back to New York, I looked up my local SGI center and connected right away. When Rob found out I’d begun practicing Buddhism on my own, he was flabbergasted. He drove to Manhattan to visit in November 1989, then again in December. I visited him in January, he proposed in February, and we were married in April. When I moved to Algonquin, friends thought I’d lost my mind. But the decision was based on daimoku and, honestly, was the easiest I’d ever made.

In 1994, I gave birth to my son, Ethan. As he neared elementary school age, I began having discussions with two other Buddhist mothers about the possibility of starting a Montessori elementary school. We all had young children and were drawn to parallels we saw between the educational philosophies of Tsunesaburo Makiguchi and Maria Montessori, which both stress the happiness and self-motivation of the child. Within just six months, we opened the doors of Muskoka Montessori, of which I was the principal for 13 years.

When Rob was diagnosed with aggressive prostate cancer in 2007, he was told he’d need to have his prostate removed or most likely die within a year. But ultimately, Rob decided not to have the operation. We went on a remarkable journey together, chanting to manifest health and happiness. Interestingly, Rob outlived his doctor’s prognosis by nine years, for most of which he enjoyed a high quality of life. In 2017, a full 10 years after the diagnosis, the cancer took his life.

I was his caregiver in his final year. Neither of us was afraid; we both knew we’d be seeing each other in a future lifetime. I was with him when he died; it was peaceful and easy.

One morning a year later, I woke up, sat straight up in bed and cried out, “I have to go back to St. Louis!” The feeling was so strong that there was no denying it. I made preparations to move back to my hometown.

At the end of September 2018, I drove across the U.S. border and have been happily situated in St. Louis ever since. The SGI community here welcomed me like family.

I must say, I know many women my age who don’t seem to know what to do with themselves. But me, I’m happy in St. Louis working for kosen-rufu!

This Buddhism, this community, has been for me and for so many in my life like water for parched earth. In the SGI I have seen what happens to people when their spirits are rejuvenated: They rejuvenate the lives of those around them. Before I pass through death’s door, I want to share this Buddhism, this Nam-myoho-renge-kyo, joyfully with as many as possible.

Q: What advice would you give the youth?

Lela Shepley-Gamble: Simple! Keep chanting! We’re a people’s movement, so you’ll run up against people who will annoy the heck out of you. Read Ikeda Sensei’s guidance, it’s powerful. Read Nichiren Daishonin’s letters, they’re beautiful. You’ll look on others—even those who push your buttons—with fresh eyes and a gentle heart. Chant about those people, and it will prove your greatest benefit.

You are reading {{ meterCount }} of {{ meterMax }} free premium articles